Solo exhibition at Titanik gallery, Turku, 2018

silver, powder coated metal

2018

solar module, found jacket, ceramic, aquarelle, rubber

2018

cut gas container, vodka, rock rose extract, sodium chloride

2018

used plastic tray

2018

truck table, green radish, cut cotton handkerchief, modified DIY antenna parts, human oils

2017

silicone, turmeric, dust, synthetic hair

2018

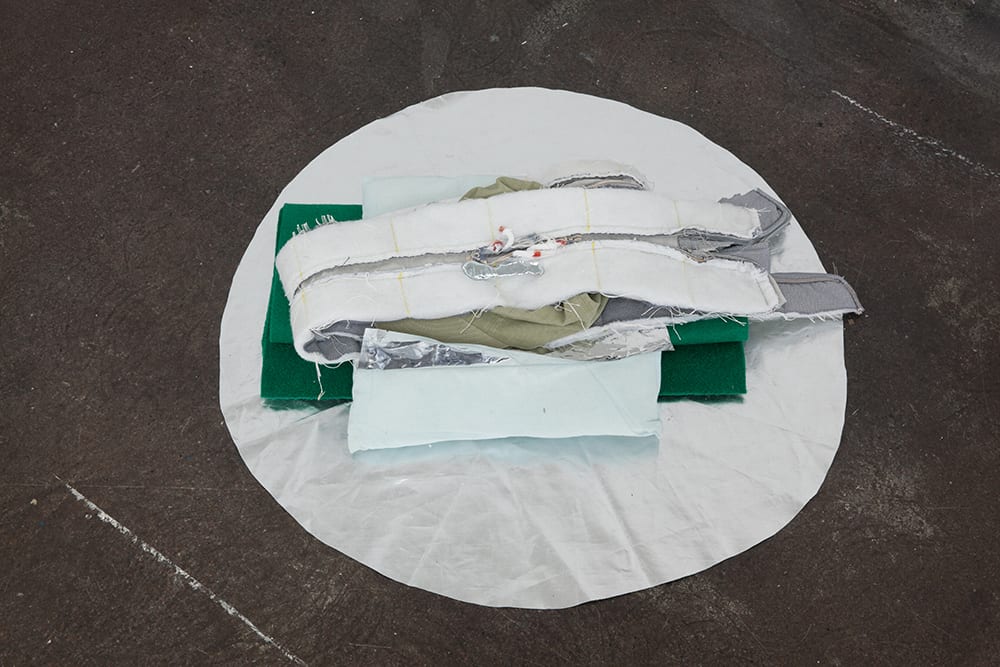

absorption boom, patches ordered from Etsy

2018

used shelve, ceramic, spraypaint, found Oak Valley towel, sticks chewed by animals, green towel, parrot cage toy bell, cage carpet, eye rinse cup

2018

unused twin carriage, papaya, cut cotton handkerchief

2018

undated (c.1990), pencil on schoolbook

2018

gallium, cap, cut mattress, found pillow, cut reflector, plastic envelope, reptile cage carpet

2018

used car carpet, papaya, cotton handkerchief cut with razorblade

2018

Every Little Pet

Giorgio Agamben has suggested that while philosophy knows its object without possessing it, poetry possesses it without knowing it. More than merely celebrating the craft as a form of knowledge production—it is the hand we should be interested in rather than the eye—the philosopher posits the residual trace of absence at the center of his aesthetic theory; all the music that has not yet been written.

What lurks in the corners of one’s vision may very well be that which is worth fumbling for. The mind has no surface, nor an inside, because it is all anchored in gestures of return. There is a straight line between a reflection and every single viewer. Tending to these direct lines can mean running one’s fingers on velvet, then on mahogany and, finally, metal. Before long, the broken, numb fingers will start distinguishing between different sensations again and recalling how thick the skin is: as thick as the table it touches, and as warm. Does it make a difference if it is a writing table or a nightstand? It is all so precarious; an act of half-attention, a compassionate one. Returning to “now” reminds the fingers of who they belong to, and that they, too, will be old one day.

Caring for every little thing. The archive has to be a perfect amalgamation of everything that needs to be preserved, only next time, try not to care so much. But you mean every single pet, don’t you?

There is an elusive tension between the simultaneity of poetic space and the preconditioned nature of perception. The eye marks its winding paths in the space. What has, however, only slowly been revealed to philosophers, shoplifters have always known. Are they not, after all, the true experts of poetic possession—the playful appropriation of what is lawfully not yours to take? The democracy of space is an illusion, one that can be easily manipulated for the purpose of business and pleasure alike. A tremendous expenditure of energy is required to maintain the boundary between possessing and being possessed.

The disappointment of someone else already having written your music. All those sequences that were reserved for you and only you.

But poetry is never a personal possession, as Susan Howe has said. The drama unfolds, but it doesn’t have anything to do with you, for your knowledge is not entirely your own; fragments seep in uninvited. The past is still here although unevenly distributed. The future is also already here, dispensed into all of those affordances they keep talking about. You know what they say.

The emergency of the everyday is a complete poetic reality that is being imposed upon whoever paces the fluorescent-lit aisles, selecting only yellow things into the green basket. The governance of order is operated in constant reference to the exception. We should exercise suspicion of the back room; in medicine, there is no such thing as a perpetual crisis.

Why buy what you could take for free? Build your nest of shiny things and find ways to have others feed the children. Occupy each moment as though you have already left, for not only do we come back but we also constantly dream of coming back. A nest is never young. Grab only that which is truly meaningful.

Let go of the anxiety that took you a lifetime to personalize.

One may ask a shoplifter for lessons on—oh I don’t want to say but—love, too. They will tell you to turn your whole body to face that what you desire and not just your head. Your chest and not your nose. They will tell you to hide by wearing your heart in your sleeve. Or, like bell hooks, “The practice of love offers no place of safety. We risk loss, hurt, pain. We risk being acted upon by forces outside our control.”

Because there is no difference between your past and the past of poetry. Don’t tell anyone what to do; even mistakes can have a life of their own.

Anna Tomi

Photos: Hertta Kiisi